|

|

|

|

|

InPrint Article

Read this article, or see other newsletter articles. March, 2006 Rand Huebsch In twenty years of exploring the etching medium, I have found that its basic premise—the exposure to acid of selective areas of metal—allows for a limitless wealth of textural effects and sculptural digressions. The following discussion of experiments—or acts of play—is organized thematically, rather than in chronological order. Unless specified, 18-gauge copper was the metal used, and ferric chloride the mordant. Textures In traditional etching, one uses the needle, a metal stylus, to "draw" and remove the waxlike protective ground from those areas of the plate that are to be etched and will eventually hold the printing ink. By drawing instead with the triangular scraper that is often used to flatten metal, and holding its edge at various angles to the grounded plate, one can create vigorous, swelling lines that are by turns sinuous and staccato. For entire areas of texture, rub different grades of sandpaper or steel wool through dry ground and then etch the plate; sometimes I randomly create several such areas, and then let the resulting proof suggest further imagery. On bare metal, stipple asphaltum on a fine brush, in a series of stop-outs and etches, to create pointillistic fields of various gray dots; because of the way that ink accrues at the edges of open-bite areas, there will be an added richness to the texture. Vary the brush marks, and overlap in the successive stop-outs.

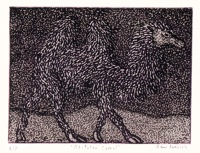

For many other marks, use lithographic crayon. To create tonal areas, draw on bare metal, then etch. The degree of crayon hardness and drawing pressure will determine the amount of particle deposited and the resulting tone. As the crayon is somewhat water soluble, it helps to reinforce the image during the etch. If applied heavily to the plate, the crayon will in fact serve as a resist; after a two-hour etch, the plate can be relief rolled, to print crayon-like lines. One can coat a sheet of thin, smooth paper with soft crayon, incise lines into that, place it face down on the bare plate, and transfer by rubbing. Those lines will then provide exposed areas of metal for etching, while the crayon material will serve as a variegated resist. Use several kinds of mark on a single plate or, indeed, on the same area of a plate (in which case the mark-making sequence is also a factor). For example, "Incidental Music" combines scraper-on-ground, litho crayon, and asphaltum stopout. Also modify the ground itself: when carborundum grit particles are mixed into liquid hard ground, the etching needle can create lines that have a texture similar to that of soft-ground drawing. Stir the ground periodically while applying it by brush, as the grit settles to the bottom of the container. Among the mixture variables are the different grit coarsenesses and the ratio of grit to ground. One can also use the scraper, with varying degrees of pressure, to remove whole areas of that ground, for an aquatint-like tone, albeit one that is coarse and erratic: the minute dots are black, rather than white as in aquatint. To obtain the nervous line that is created by drawing on a plate covered with old, brittle ground, mix asphaltum with mineral spirits; once dry, it tends to splinter along the edges of exposed metal during the drawing. Stencils and Shadows For an installation based on Goya's etching "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters," in which winged phantoms taunt a sleeping figure, I made shaped pieces from used aluminum lithography plates. After coating a given plate with ground, I drew the outline of the intended shape with white Caran d'Ache crayon, then followed that line with an incising needle, to remove enough ground for a continuous 1/8"-wide area of exposed metal. After a three-hour etch, the shape was "scissored-out" from the surrounding plate. The still-grounded piece was then incised with many texture lines and returned to the acid. After cleaning the piece, I applied ink to the etched lines and let it dry, to accentuate them. The seven finished pieces ranged in diameter from 1 1/2 feet to 3 feet and were hung by thin wire from ceiling pipes in the corridor leading to the print shop where they were made. Please note: some acrid fumes were produced in the etching process, and it may be safer to etch aluminum with the fluoride that is sold for that purpose. I have made other, smaller shaped pieces to use as stencils of various kinds, and used the standard image-transfer method and etching-needle drawing. For these pieces I generally choose brass—obtainable at metal-surplus stores or jewelry-supply shops—as it is sturdier than copper, an important consideration when the element is to be handled often, has open-work areas, and is of the thickness of heavyweight printing paper. Accordingly, for the acid resist on the reverse side of the metal I apply liquid ground: the pieces are so thin and sometime have such large open areas that a post-etch removal of contact paper might cause them to buckle. For "Daemon," I used several shaped pieces, and with each one tried various methods: stencil printing with stiff brush, relief inking with press printing, and blind embossing (the embossing is very subtle and reminiscent of the Karazuri impressions in Japanese woodcuts).

Similar pieces were elements in a black-painted foam-core toy theater (11"h x 15"w x 11"d) that was also inspired by "The Sleep of Reason" etching. The metal open-worked gargoyles were suspended by thin wires from a disk that was adjacent to the theater's ceiling and thus hidden from view. That disk was glued perpendicular at its center to a wooden dowel that went through the "roof" of the theater and that was glued to a parallel disk on top of the structure. A second dowel was glued perpendicular to that upper disk, near the edge. It served as the handle with which the viewer could rotate the device, so that the hanging figures formed a nightmare carousel, casting filigreed shadows as they flew around a sleeping seated foam-core man on the theater's stage. Because the turning device resembled the levigator that is used for grinding lithography stones, it alluded to another print process that Goya used.

To make inexpensive stencil-projection pieces for a little-theater production, I etched thin 3" x 3" brass sheets in undiluted 38-Baume ferric chloride for two hours. Called a "gobo" and now made commercially by laser, this kind of device has long been used in lighting design, usually to subtly indicate leaf-dappled surfaces. However, as the play was allegorical and not presented on a proscenium stage, I designed images that were very specific and emblematic. The theater lanterns that held the gobos, along with colored light gels and scorching 500-watt bulbs, were suspended from an overhead grid many yards from the stage area. When each of the six gobos was projected onto one of several cloth panels onstage, its shadow image was enlarged to six feet by eight feet, and that projection served as the "set" for a particular scene. The images ranged in style from naturalistic (a magenta stained-glass window for a church scene) to the highly iconic (including a deep-red wolf's head, fangs bared, for a scene in which a powerful official menaces a subordinate, and a network of letters and numbers, superimposed on the actors, to represent a state-controlled library). As the visual artist is usually a solitary worker, one reason that I enjoyed the theater project was the chance to collaborate with others—to determine, for example, the optimal use of the theater space, the best placement of the gobo lanterns, and the duration of the lighting dissolves from one scene to the next. Other Presentations Artist's books provide, literally, an extra dimension for display of etchings. (Often I have made embossings for the books, and that process is described in the Maryland Printmakers' newsletter article from March 2005 Making An Impression Secrets of Embossing Shared). When using the accordion book, I often treat each panel as self-contained, as in "Reptiles," designed to evoke the natural histories of the 17th and 18th centuries. In "Biblion," however, there is a continuous narrative from first panel to last, as in Japanese folding screens. Like a screen, the accordion book can be viewed from front and back, and for "Aviary" I hand-colored both sides of the book's embossings by rubbing Caran d' Ache crayon over the surfaces. When there is to be an embossed image that carries over from one panel to the next, reserve a thin seam of ground-covered metal, along what will be the fold, so that later it will be easier to score the printed sheet. Originated in the Italian Renaissance for studying perspective, the tunnel book is another useful format. It consists of a series of parallel image-bearing panels, all of which, except for the solid back one, have cut-out areas. The panels are attached on two sides to accordion-folded strips, allowing the book to stand upright and present a theater-like scene. The format entails a nice tension between the autonomy of each panel and that of the entire book, and I like the fact that the scene alters when the viewer changes position vis-a-vis the book. (An illustrated article about the tunnel book appears in the e-journal, Bonefolder).

I consider my several shadow-puppet plays to be an offshoot of etching, for the puppets were influenced by, and in turn influenced, those etching projects that also used stencil, cast shadow, and movement. I made the puppets of thin cardboard and wooden dowels, and they had cut-out areas like those of the Goya theater's flying creatures. And, just as a printing plate serves as the matrix for an image, so does a shadow puppet: unlike a marionette, it is manipulated behind the screen—thus the audience sees not the puppet itself, but the shadow that it produces. My teaching of etching to young people has also been an extension of my interest in the process; in addition, the two educational print shows that I curated for the New York Hall of Science in 2001 and 2003 arose out of my fascination with printmaking, and a wish to promote greater awareness of it. Contact Rand Huebsch at rahuebsch@earthlink.net |