An Exhibition Evolves 'Picturing

Animals' marries animal imagery and the process of printmaking in an

exciting new exhibition. Rand Huebsch guides us through the show

In the spring of 2001, the New York Hall of Science presented

"Picturing Animals: Contemporary Printmakers Create Natural History

Images." In creating that show, I was to discover that curating, with

its revisions and its manipulation of material, has parallels with

printmaking, my primary creative activity. While faithful to the

initial concept, the finished show would represent a months-long

process of evolution.

In the spring of 2001, the New York Hall of Science presented

"Picturing Animals: Contemporary Printmakers Create Natural History

Images." In creating that show, I was to discover that curating, with

its revisions and its manipulation of material, has parallels with

printmaking, my primary creative activity. While faithful to the

initial concept, the finished show would represent a months-long

process of evolution.

Laying the Groundwork

For many years, two strong interests of mine have been animal

imagery and the process of printmaking. "Picturing Animals" was

conceived as an exploration of the centuries-old tradition that links

them. An additional aim was to present the work of contemporary

printmakers working within that tradition, some using established

techniques, others experimenting with recently invented materials. In

considering these aims and writing a proposal, I realised that this

educational show would require two sections: historical and

contemporary. Each would comment on the other; together, they would

cohere into a larger, meaningful whole.

Because the New York Hall of Science has an educational mission, it

seemed an ideal venue for the show. The Hall is a science and

technology centre, featuring more than 225 permanent interactive

exhibits. It was my good fortune, when first presenting the proposal in

the summer of 2000, to speak with Dr. Marcia Rudy, Director of Public

Programs/Special Events. Her enthusiasm for the project was crucial, as

were her equanimity and attention to detail during its evolution. With

the Hall's entry, there was a shift in the project's focus.

In the initial proposal, all of the images for the show's historical

section had been European. Now, that section had to represent a broader

range of cultures, as the Hall is located in Queens, the most

ethnically diverse community in the United States. Expanding the show's

scope allowed for a larger listing of processes, including the elaborate Japanese stencils called katagami, rubbings from Han Dynasty stamped bricks, and adinkra, African fabric-stamp blocks carved from the rinds of calabashes.

That revision was among the first of many editorial choices. For

example, the wonderful Durer rhinoceros, which I had considered for the

relief-printing description, seemed an overly familiar image. Instead,

I used Hans Grien Baldung's dynamic woodcut of seven horses fighting.

A unit called "The Evolution of a Print" was to include dramatically

different states of Picasso's bull lithograph. It did not appear,

partly due to space limitation, but also because it would have skewed

the show's balance. Sometimes the relationship of images was the key:

for their similarity of pose and contrast in style, I chose two polar

bears - a 19th-century French etching and a 20th-century Inuit stone cut. In order to study image possibilities together, I taped them to an expanse of wall in my apartment.

The Exhibition

1. The Historical Section

To accompany the text of this section's five units, there were thirty

animal prints in reproduction, from scientific illustration to images

of personal mythology. "What is a Print," the first unit, discussed

basic concepts, citing the rubber stamp as a familiar example of a

printing matrix. A photo of an Ice Age cave painting

showed not only man's early depiction of animals, but also hand

stencils - possibly the first kind of printmaking. Next, "Processes"

gave concise definitions of four printing techniques: relief (woodcut),

intaglio (including etching), lithography, and stencil

(screenprinting). In keeping with the Hall's focus on science, the text

alluded to technologies; it mentioned, for example, that intaglio

printing may have derived from the decorative incising used in metal

working.

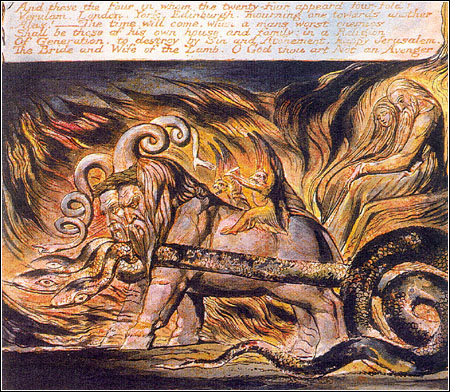

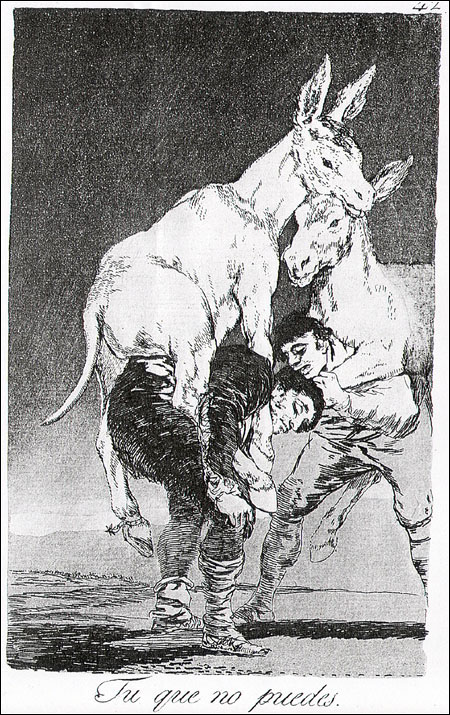

"Man

and Animal" owed its genesis to Choensai Eishin's woodcut of a

falconer, which I came across while doing research at the New York

Public Library. This image gave rise to the idea for a unit of eleven

prints that depicted man/animal interactions. They ranged from John Muafangejo's lion hunters and Toulouse-Lautrec's jockey, to Goya's satirical human-riding donkeys and William Blake's human-headed quadrupeds pulling a chariot. "Man

and Animal" owed its genesis to Choensai Eishin's woodcut of a

falconer, which I came across while doing research at the New York

Public Library. This image gave rise to the idea for a unit of eleven

prints that depicted man/animal interactions. They ranged from John Muafangejo's lion hunters and Toulouse-Lautrec's jockey, to Goya's satirical human-riding donkeys and William Blake's human-headed quadrupeds pulling a chariot.

The last two units served to emphasise printmaking's availability and

to act as a bridge to the contemporary work. One segment had captioned

photos of high school students as they made etchings for a

collaborative book, a copy of which was on display. The other segment

had text that instructed viewers in designing, carving, and printing

their own rubber stamps; some of the modern printmakers provided

rubber-stamp images for that text.

2. The Contemporary Section

This section displayed thirty-five prints on a 65-foot wall that

stood at a right angle to the historical section's 14-foot one. In

addition to me, the contemporary artists were Susanna Bergtold, Donna

Evans, John LoCicero, and Deborah Tint. Twelve different processes were

represented. The traditional ones were aquatint, etching, linocut,

lithography, mezzotint, wood engraving, woodcut, and Ukiyo-e. The new

techniques, which used recently invented materials, were alumigraph,

carborundum aquatint, gessoprint, and silicone intaglio. A series of

text panels explained many of the processes.

The development of this section had been largely concurrent with the

historical one. It was here, in particular, that the project's

collaborative aspect came into play. I had worked with these artists

before. I respected their art work and also knew that they would

contribute in the necessary planning meetings. Their input would prove

helpful when I wrote the text of the exhibition proposal and, later,

that of the show itself.

For the exhibition, each artist made a number of decisions, such as

selecting his or her images and whether to mat or to float the work

under the plexiglas sheets. Each artist chose several printmaking tools

for inclusion in the nearby display case. Artist statements served to

reveal the thinking behind the work. They ranged in tone from the

lyrical - "Animal familiars (squirrels, pigeons, sparrows,

crows, dogs, and cats) resonate within me as recallable rhythms of

touch and sight", to the humorous - "The woodcuts of reptiles are my

tribute to the delightful scientific illustrations of the Age of

Exploration (well, invasion)".

Several of the artists made new work specifically for the show. One

made drawing visits to the Queens Wildlife Center, then used those

sketches as the basis for his prints. While intending to create new

images, ultimately I used pre-existing work. This was not due to lack

of time. My creative focus had been the shaping of the exhibition. The

research, writing, and collaborative process were the elements with

which I worked, and I hope that the resulting show will have a life

beyond its first venue.

|

|

|

|

|